where y denotes the final good, K denotes the physical capital stock, H denotes the human capital stock, A is the level of technology and L denotes labor supply. The key parameters of interest are \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) , which represent the rate of return on physical and human capital stock. When \(\beta = 0\) , Cobb–Douglas production function in Eq. (1) nests the basic Solow model without human capital. We assume that the production function is twice continuously differentiable with positive but diminishing marginal products and constant returns to scale, which implies that:

$$F_We also assume that the production function satisfies the Inada conditions and provides for the existence of the inner equilibria:

In this particular setup, countries differ in the physical and human capital savings rates, \(s_\) and \(s_\) , population growth rates \( \mathord <\left/ <\vphantom >>> \right. \kern-0pt> >> = n\) , and the growth rates of technology \( > \mathord <\left/ <\vphantom > = g_ >>> \right. \kern-0pt> = g_ >>\) , and in the initial level of technology. Instead of the aggregate capital stock, we are primarily interested in the capital–labor ratios since the assumed technology takes the Harrod-neutral labor-augmented form, AL. For j-th country, capital–labor ratios are defined as follows:

$$\left( > \right)_ = \frac <Using steady-state equilibria in Eqs. (4) and (5) together with the capital–labor ratios in Eqs. (2) and (3), per capita output in the neighborhood of the balanced growth path is as follows:

$$y_where, following Mankiw et al. (1992), we assume that countries are different in technology level, leading to different values of initial A, but they share the same common technology growth rate, \(A_ = \bar_ e^ >>\) . Notice that if g is not equal across countries, per capita income will diverge. Using the balanced growth path of per capita output and assuming Mankiw et al. (1992) technology growth dynamics, we obtain the following balanced growth path of income for country \(j = 1,2, \ldots J\) :

where \(\varepsilon\) denotes the stochastic disturbances capturing the random error term. One of the major challenges in estimating the balanced growth Eq. (7) is that the level of technology is unobserved to the econometrician, and is, thus, absorbed by the random error term. It is also correlated with the capital stock or capital accumulation, which implies that estimating Eq. (7), invokes standard omitted variable bias. Even though one might assume that the level of technology is orthogonal to random error term, \(\bar_ = \varepsilon_ A\) and \(E\left( >> \right) = 0\) , such assumption has been questioned extensively. Since technology differences are hardly orthogonal, the omitted variable bias and the potential reverse causation between capital stock and growth renders the baseline OLS coefficients in Eq. (7) biased upward. Our partial remedy is to add the vector of control variables to the standard augmented Solow growth equation and the full set of technology shocks that are common to all countries but may differ with respect to the magnitude. Although imperfect, such an approach can partially alleviate the omitted variable bias and allow us to estimate the structural parameters consistently.

4 Long-run development under counterfactual de Jure and de Facto institutional design: an empirical model

This section presents an empirical model of Argentina’s long-run development under counterfactual institutional design using a synthetic control estimator to tackle the long-run effects of institutional breakdowns.

4.1 Long-run development with de Jure and de Facto political institutions

The perplexing political history of Argentina and its rampant institutional instability invoke two fundamental dilemmas (Acemoglu et al. 2003). First, what would have happened to Argentina’s long-run economic development had it managed to enshrine a set of de jure and de facto political institutions comparable to those of the United States in its constitution and had such an institutional framework actually been enforced? In the absence of institutional breakdowns, would Argentina have remained a rich country? Would its path of economic growth and development have been characterized by a similar slowdown had it established and maintained US-style de jure and de facto political institutions such as competitive polities, an independent Supreme Court, and open access to collective action for the broad cross section of society rather than only for the privileged few? Second, how would Argentina’s path of long-run development have changed if it had established US-style de jure and de facto political institutions at various junctures in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when it took an unfortunate turn toward institutional breakdowns rather than developing a genuine system of checks and balances?

The aim here is to build a counterfactual scenario of institutional breakdowns, to construct the path of long-run development in the absence of such breakdowns, and to estimate consistently this absence’s contribution to long-run development. The absence of breakdowns is simply characterized by the alternative set of de jure and de facto political institutions put in place instead of the existing ones, drawing on Argentina’s unique path of departure from a rich country to an underdeveloped one.

For a nonrandom sample of \(j = 1,2, \ldots J\) countries across t = 1,2,…T years, the basic fixed effects relationship that takes place is:

where y is the real per capita gross domestic product (GDP) for country j at time t, \(\varOmega\) is a constant term, the set of country-varying coefficients \(\mu_\) captures the set of country fixed effects unobserved by the econometrician, \(\phi_\) is the set of technology shocks common to all countries, and \(\left[ \cdot \right]\) is the Iverson bracket in the set of indicator functions, with the vector of country-level and time-level indicator functions capturing the unobserved effects across countries and over time. The key coefficients of interest are \(\hat_\) and \(\hat_\) , which denote, respectively, the contributions of de jure and de facto political institutions to long-run development. The vector \(<\mathbf

The key challenge posed by the empirical setup hinges on the reliability of the standard errors, which critically affect the consistency of the estimated responses of long-run development to the changes in the de jure and de facto political institutions. A major threat to the proposed empirical design is related to the possibility of multiple serially correlated stochastic disturbances both across and within countries. The serial correlation in the unobservable component could lead to massively underestimated standard errors, which would imply that the underlying null hypothesis on the effects of de jure and de facto political institutions was over-rejected because of the underestimated standard errors, which would invoke the Kloek–Moulton bias (Kloek 1981; Moulton 1986, 1990). In the absence of mitigation of the multiple sources of serially correlated stochastic disturbances, the serial correlation in unobservables can persist even when the unobserved country-fixed effects and time-fixed effects are controlled for. Valid standard errors and the underlying inference regarding the true contribution of de jure and de facto political institutions critically require overcoming the one-way clustering of standard errors using a multiway clustering scheme that allows the parameter estimates to be robust against within-country and between-country serially correlated stochastic disturbances (Bertrand et al. 2004; Kézdi 2004).

To mitigate the distribution of serially correlated stochastic disturbances, the empirical setup uses a non-nested multiway clustering estimator from Cameron et al. (2011). The standard errors are simultaneously clustered at country and year levels using the two-way error component model with independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) residuals (Moulton 1986; Davis 2002; Pepper 2002) instead of one-way clustering (White 1980, 1984; Pfeffermann and Nathan 1981; Liang and Zeger 1986; Arellano 1987; Hansen 2007; Wooldridge 2003; Cameron and Trivedi 2005), which may lead to the over-rejection of the null hypotheses, rendering the standard errors and parameter inference unreliable.

4.2 Constructing the counterfactual scenario

I construct the counterfactual distribution and set out to examine the alternative path of long-run development in the absence of institutional breakdown by using a synthetic control setup whose purpose is not to tackle the direct effects of policy changes. Suppose J + 1 countries are observed over t = 1, 2,…, T periods, with Argentina being the country affected by the institutional breakdowns and with other countries \(\left\ < \right\>\) being unaffected by such breakdowns. Suppose the institutional breakdown (which affects only Argentina and leaves the other J countries unaffected) occurs at period \(T_ + 1\) , \(1 < T_+ 1 < T\) . Let \(\ln y_^\) denote the per capita GDP for country i at time t in the absence of the breakdown, and let \(\ln y_^\) denote the per capita GDP observed for country i at time t if the country were exposed to the breakdown. Furthermore, assume that the breakdown had no effect on the outcome before it took place, \(Y_^ = Y_^\) for all i, and \(t < T_+ 1\) . The aim is to estimate the effect of institutional breakdowns over time for the treated unit. If \(\alpha_ = \left( <\alpha_,\alpha_ <

where \(\ln y_\) denotes the observed per capita GDP and \(\ln y_^\) is the counterfactual per capita GDP in the absence of institutional breakdowns. It is assumed that \(\ln y_^\) follows a latent factor model for all i = 1, 2,…, N of the following form:

$$\ln y_<1,t>^ = \delta_ + \theta_ <\mathbfwhere \(\delta_\) is an unobserved factor common across all countries, \(<\mathbf

Let \(W = \left( , \ldots ,w_ > \right)\) be a vector of weights with \(w_ \ge 0\forall j\) , where each value of W represents a potential synthetic control. For a given W, the per capita GDP for a synthetic control at time t is

where it is assumed that \(\exists W^\) is such that the synthetic control is set to match the treated unit in the pre-breakdown period so that \(\sum\nolimits_^ ^ > Y_ = Y_ \quad \forall t \in \left\ < > \right\>\) and \(\sum\nolimits_^ ^ X_ = X_ >\) . Footnote 7 If the conditions are met, the synthetic control associated with \(W^\) replicates the missing counterfactual. The baseline synthetic control model (Abadie et al. 2010) for a single treated unit is adopted. Hence, an approximately unbiased estimator of \(\alpha_\) is then given by

$$\hat_ = \ln y_ - \sum\limits_^ ^ \ln Y_ = \ln Y_ - \ln Y_ > ,$$where a nested weight matrix is used to minimize the root-mean-square prediction error and compute a reasonably unbiased synthetic match of the treated unit. Compared with difference-in-differences analysis, the synthetic control method imposes less restrictive functional assumptions on the estimation process. Under a data-driven approach to the counterfactual estimation, \(W^\) forces the data to exhibit parallel trends in the pre-breakdown period, because the validity of the synthetic estimates crucially hinges on the parallel trend assumption.

5 Data

This section briefly discusses sample selection, outcome variables, data used to construct the indices of economic and institutional development, and coding of institutional breakdowns.

5.1 Outcomes and samples

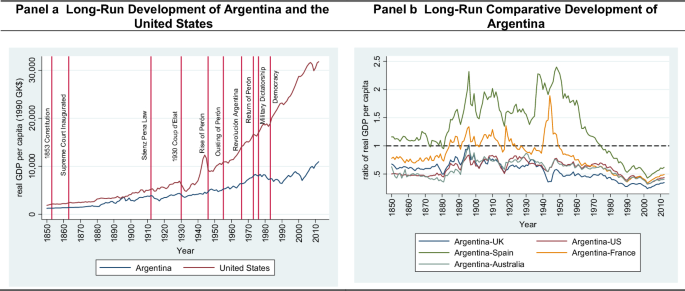

The sample comprises 28 countries for the period 1850–2012. The measure of long-run development, as well as the outcome variable, is real per capita GDP at 1990 constant prices, denoted in Geary–Khamis international dollars from Bolt and Van Zanden (2014) following earlier work by Maddison (2007a, b). Because the focus is on Argentina, the data on per capita GDP stretch back to 1850 and are based on earlier work by economic historians Bértola and Ocampo (2012) and Prados de la Escosura and Sanz-Villarroya (2009). The annual data are used to overcome the compression of long historical periods (Austin 2008) and the subsequent bias in the direction of the underlying effects of de jure and de facto political institutions. For the pre-1870 period, a simple linear interpolation is used between 1850 and 1870 to yield an overall annual variation in per capita GDP over time. Figure 1a, plots the path of Argentina’s per capita GDP against that of the United States for the period 1850–2012. At face value, the evidence clearly suggests that until 1900 Argentina managed to parallel the US per capita output level. Following a relatively smaller output decline during the Great Depression in the early 1930s, Argentina embarked on a path of comparatively greater output stagnation relative to the United States and a markedly slower rate of economic growth, especially in the years following the 1930 military coup. Figure 1b, maps the long-run development of Argentina compared with other countries.

5.2 De Jure and de Facto political institutions: a factor analysis

The definition of institutions that is used in this paper relies on North (1990), whereas the delineation between de jure and de facto political institutions is based on Feld and Voigt (2003), Pande and Udry (2005), Acemoglu and Robinson (2006a), Robinson (2013), Shirley (2013), Voigt (2013), Földvári (2016), and Spruk (2016). In their broadest form, the de jure political institutions capture the set of rules allocating political power through a formal institutional framework such as electoral law and the constitution. The de facto political institutions denote the ability to engage in various forms of collective action and contest the political power of the elites. The distinction between de jure and de facto political institutions is crucial, because the balance of the de jure and de facto political power of the elites tends to shape the structure and equilibrium of economic institutions and, together with procedural details, bears directly on economic performance (Summerhill 2000). Acemoglu and Robinson (2006a) suggest that both sets of political institutions exert a strong form of temporal persistence. “Put differently,” they write, “when the elites who monopolize the de jure political power lose this privilege, they may still disproportionately influence in politics by increasing the intensity of their collective action (e.g., in the form of greater lobbying, bribery, or downright intimidation and brute force), and thus ensure the continuation of the previous set of economic institutions” (Acemoglu and Robinson 2006a, 326). Footnote 8 In contrast, McCloskey (2016, 69) believes the various layers of institutions coincide with a “great deal” of social ethics, which is needed to support bourgeois virtues as the precursor for sustained and broad-based institutional development. Footnote 9

In this paper, the data on the de jure political institutions are from the Polity IV Annual Dataset (Marshall et al. 2013), which contains the quantitative indicators of the formal regime characteristics as a proxy for the distribution of de jure political power. The underlying polity index comprises six subindicators that capture the distribution of de jure political power: (a) competitiveness of executive recruitment, (b) openness of executive recruitment, (c) executive constraints, (d) de jure competitiveness of political participation, (e) formal regulation of political participation, and (f) competitiveness of political participation (Treier and Jackman 2008; Marshall et al. 2013). The data on the de facto political institutions are from Vanhanen’s index of democracy in the Polyarchy Dataset (Vanhanen 2000, 2003) for the period 1850–2012 and are used to construct the comparable indices of de facto political institutions in the long-term perspective. In its broadest form, the index of democracy captures the ability of nonelites to engage in various forms of collective action and to contest the political power of the elites in free and fair regular elections. The index of democracy comprises two underlying subindices: (a) the index of political competition and (b) the index of political participation. First, the index of political competition is constructed on the basis of the percentage share of votes cast for smaller political parties and independents in parliamentary elections or their share of the number of seats in the parliament. The index is constructed by simply subtracting the largest party’s vote share from 100 percent. Second, the index of political participation is composed of the percentage of the adult population that voted in the elections, which broadly reflects the ability of nonelites to contest the political power of elites and to engage in the process of collective action.

The use of voting rates as an indicator of de facto political institutions has been the subject of scholarly criticism. Many avenues besides voting rates exist for influencing collective action. In this respect, a political competition index might overtly neglect proportional representation versus a first-past-the-post system, because the index yields higher values for systems having a greater number of small parties. Hence, countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States automatically score much lower on a de facto institutional metric than do countries with proportional representation, even though they are stable democracies that recognize the rule of law, possibly to a much greater degree than many countries with proportional representation. Despite such easily acknowledged limitations, voting rates provide an easily trackable indicator of de facto political rights that can be compared across countries and over time. Although a measure of informal norms would be more appropriate for such purposes, no such indices or data currently exist for the greater part of the time series being studied in this paper.

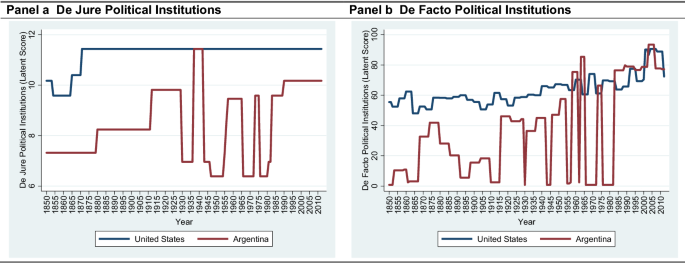

My aim is to construct consistent and both internally and externally valid indices of de jure and de facto political institutions in which the maximum temporal and spatial variance is extracted from each underlying component (Bollen 1990; Pemstein et al. 2010). To this end, I have used the factor analytic (FA) approach to construct the de jure and de facto indices of political institutions. Using the FA approach, I have constructed two major latent indices of political institutions from the underlying Polity IV and Vanhanen ID components. The two indices are constructed from eight different subindicators. The rotated components indicate that the first dimension correlates strongly with four Polity IV indicators, which reflects the structure of de jure political institutions. The second major dimension correlates strongly with political competition, executive constraints, and political participation, which is characteristic of de facto political institutions. Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach 1951) indicates that both latent indices exhibit a high degree of internal consistency. For the latent index of de jure political institutions, α = 0.81, and for the latent index of de facto political institutions, α = 0.70, which indicates very little structural inconsistency and measurement error. In Fig. 2, the path of de jure and de facto institutional development is presented for Argentina and the United States. The figure clearly shows that Argentina’s path of de jure and de facto institutional development is characterized by persistent instability, reversals, and breakdowns.

5.3 Institutional breakdowns

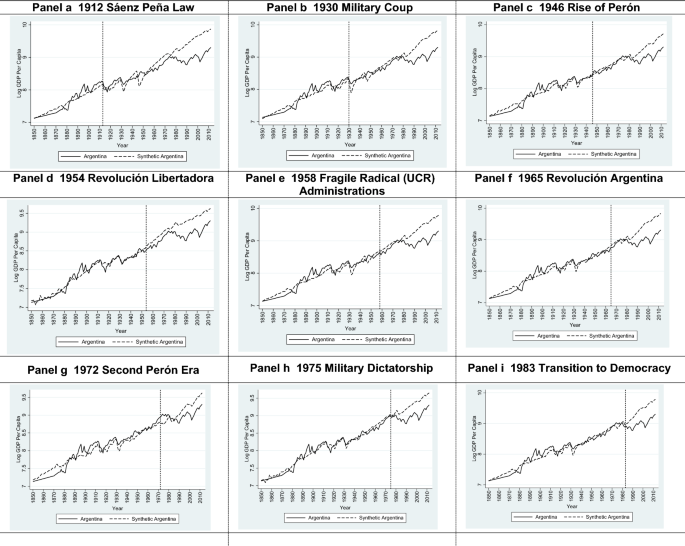

Argentina’s institutional breakdowns are gauged by abrupt shifts in both indices of de jure and de facto political institutions discussed earlier. To examine the contribution of institutional breakdowns to the country’s long-run development, one must focus on the major turning points in Argentina’s institutional history in the aftermath of the 1853 Constitution that eventually led to the series of institutional breakdowns. Because the goal is to construct the counterfactual scenario of long-run development without institutional breakdowns, the proposed empirical strategy does not facilitate the measurement of breakdowns from a substantive point of view. The period in which the breakdown of checks and balances and the democratic institutions evolved is used as a starting point to build a counterfactual scenario. The counterfactual scenario can perhaps best be summarized in a single dilemma: what would have happened to Argentina’s long-run development had its de jure and de facto political institutions, such as competitive polity, access to collective action for nonelites, and an independent Supreme Court, followed developments in parallel countries that did not experience breakdowns, starting with the 1930 military coup? The counterfactual series on de jure and de facto political institutions are constructed by building eight specific counterfactual scenarios that meet the de jure and de facto institutional design. Specifically, eight different dates are considered in the counterfactual scenario: (a) the 1930 coup, (b) Perón’s rise to power (1946), (c) the Revolución Libertadora (Liberating Revolution) that resulted in the ousting of Perón (1955), (d) the beginning of a period of fragile UCR administrations and political instability (1958), (e) the Revolución Argentina (Argentine Revolution) and the shift to an authoritarian and bureaucratic state (1966), (f) the second Perón era (1972), (g) the onset of military dictatorship (1976), and (h) the formal transition to democracy (1983). The 1912 Sáenz Peña Law is used as a robustness check. Using these dates allows the model to project Argentina’s long-run development in the absence of institutional breakdowns occurring within these dates—that is, if, instead, Argentina had followed the de jure and de facto institutional development in plausibly similar countries. Table 1 gives a summary of the institutional breakdowns used to construct the counterfactual scenario, along with Argentina’s mean per capita GDP level at the breakdown period in question, the growth rate, and the standard deviation.

6.4 Robustness checks

This section briefly discusses the alternative difference-in-differences (DD) counterfactual setup of the long-run development model as a robustness check on the validity of synthetic control estimates.

6.4.1 Difference-in-differences counterfactual setup

As a robustness check on the validity of synthetic control estimates, the difference-in-differences effects of Argentina’s institutional breakdown on long-run development were computed and the set of counterfactual estimates was constructed. A calibration of the DD parametric estimates is performed to examine the alternative paths of Argentina’s development under two plausible assumptions: (a) the absence of institutional breakdowns and (b) the adoption of US-style de jure and de facto political institutions over a 15-year transition window.

Let \(i = 1,2, \ldots N\) index the number of countries in the sample. Suppose the de jure and de facto institutional breakdowns take place in country j at time t. Assume country j at time t + 1 embarks on a different institutional path from a nearest-neighbor country with similar observable characteristics. First, to gauge the effects of institutional breakdowns, use the following equation to show the underlying counterfactual distribution of the de jure and de facto set of political institutions:

where the set of de jure and de facto political institutions in the j-th country in the postbreakdown years is replaced by the set of political institutions from the i-th benchmark country—in this case the United States. Second, invoke the core fixed effects long-run development in Eq. (8), and consider the estimated de jure and de facto coefficients. Third, for Argentina as the treated unit, construct an alternative de jure and de facto institutional time series, where the level of development of the de jure and de facto political institutions moves to the US level in t + 1 during the 15-year transition period. Fourth, use the de jure and de facto long-run development point estimates, and compute the path of long-run development with the alternative time series in the postbreakdown period conditional on the observed covariates and their point estimates in Table 3. Using the spliced de jure and de facto institutional time series for Argentina, one can compute the counterfactual path of long-run development as:

where \(\overset<\lower0.5em\hbox<$\smash<\scriptscriptstyle\frown>$>>_^>\) is the counterfactual path of long-run development for the j-th country (Argentina) at time t; \(\tilde_\) and \(\tilde_\) , respectively, denote the point estimates for de jure and de facto political institutions to long-run development from Eq. (3.1); \(\tilde<\mu >_\) denotes the shift in the intercept \(\tilde\) triggered by unobserved country-level effects, which varies across countries; \(\tilde<\phi >\) denotes the shift in \(\tilde\) triggered by the time-varying technology shocks common across all countries; \(\tilde\) indicates the estimated effects of long-run development covariates different from political institutions; and \(\Delta_\) denotes the cyclical variation in \(y\) captured by the log first differences of per capita GDP that take place even with the alternative de jure and de facto institutional design. By default, Eq. (14) implies that the counterfactual long-run development series exactly matches the actual one in the pre-breakdown period but tends to offset it in the postbreakdown period.

In Additional file 1: Table S1 summarizes the DD effects of institutional breakdowns on Argentina. If Argentina had had US-style de jure and de facto political institutions in place since 1850, the counterfactual estimate implies that its long-run per capita output would have been 45 percent higher than the actual one by the end of the estimation period. Such a sizable gain in long-run growth and development following the US-style institutional design implies that Argentina’s per capita output relative to that of the United States would rise from 34 percent to roughly 50 percent. The DD estimates of Argentina’s long-run development without institutional breakdowns are slightly smaller but roughly similar to the synthetic control estimates in Fig. 3 and Table 5.

7 Conclusion

This paper exploits moments of institutional breakdown to consistently estimate the contribution of de jure and de facto political institutions to long-run development. Drawing on Argentina’s extensive historical bibliography, the empirical strategy used here identifies the moments of institutional breakdown and builds a counterfactual scenario assuming Argentina developed de jure and de facto political institutions such as those that developed in similar countries, including competitive polity, genuine rule of law, checks and balances, and an independent Supreme Court. The 1853 Constitution enshrined many principles from the US republican model, and Argentina embarked on the path of its Belle Époque. It achieved remarkable rates of economic growth but never finished its transition to democracy. Decades of electoral fraud, political malfeasance, and legislative malapportionment were put to a halt in 1912 upon the passage of the Sáenz Peña Law, which outlawed fraud and introduced secret, compulsory male suffrage. Although democracy tends to accompany the rule of law and greater transparency, by the same token, the Sáenz Peña Law also sowed the seeds for income and wealth redistribution and helped to pave the way for the populist-style public policies that also condoned the institutional breakdowns that followed. Argentina’s transition to democracy was formally infringed in the 1930 military coup, which precipitated a decade of electoral fraud, brought about the demise of checks and balances, and later led to Juan Perón’s rise to power. This paper shows that Argentina’s departure from the system of checks and balances and its abandonment of the rule of law triggered a series of persistent institutional breakdowns and held long-lasting implications for the country’s growth and development for many years ahead.

Had the institutional breakdowns not occurred and had Argentina followed the trends established in similar countries in developing de jure and de facto political institutions, its per capita output would have improved dramatically. In the long run, the absence of institutional breakdowns is associated with a 45 percent increase in per capita output. Such a large gain is the equivalent of Argentina’s departure from a middle-income country into the ranks of Spain and Italy. In the counterfactual scenario, the long-run benefits of an absence of institutional breakdowns are pervasive, robust, and large-scale improvements in long-run development. Had the Sáenz Peña Law not facilitated populist-style income and wealth redistribution, the synthetic control estimates here imply that today Argentina’s per capita income would approach 62 percent of the US level, which is comparable to that of New Zealand or Slovenia. Instead, Argentina perpetuated nearly a century of institutional instability that undermined the security of property rights, increased transaction costs, and essentially led to the abandonment of the rule of law. Starting with the rise to power of Perón and his influential wife Eva, Argentina embarked on an irreversible path of populist social and economic policies and divide-and-rule politics that ignited Argentina’s decline. The institutional breakdowns triggered by powerful elites were chiefly characterized by uninterrupted forced resignations of Supreme Court justices, declaration of economic and political emergencies, nationalization of firms, prosecution and torture of political opponents, nullification of the 1853 Constitution, rampant government favoritism, and media censorship.

Had the 1930 military coup never happened, and had Argentina avoided the subsequent institutional breakdowns and the populist Peronist-style divide-and-rule politics, the synthetic control and difference-in-differences estimates described herein imply that the country would have experienced a robust upward growth. In the absence of institutional breakdowns, Argentina’s per capita income would have approached the ranks of New Zealand, Spain, and Italy.

The implications of this analysis are that having de jure and de facto political institutions borrowed from a benchmark country such as the United States would not have prevented Argentina’s century of decline following the US growth spurt. The limited data on the layers of economic, legal, and other types of institutions preclude a systematic counterfactual investigation of an alternative development path with a different set of economic and legal institutions and public policies than the actual ones. From the normative perspective, the analysis highlights important interplay between the de jure and de facto political institutions, institutional breakdowns, and long-run development. First, the effects of institutional breakdowns such as the forced resignation of Supreme Court justices are unlikely to disappear. They hold negative, long-lasting implications for the path of growth and development and may trigger the adverse side of path dependence. Second, technological and development breakthroughs are unlikely to be nurtured by broad-based and pluralist de jure and de facto political institutions per se because such institutions may be insufficient to create a framework based on secure property rights and low transaction costs that could underpin the path to sustained growth. Third, the onset of institutional breakdowns typically invokes rampant government favoritism of powerful groups in the absence of constraints on the various sources of power. Such favoritism—first in the form of the populist-style policies that proliferated under Perón and second in the form of shifts back and forth between democracy and dictatorship—proved detrimental, as it condemned Argentina to comparative decline and economic stagnation, expanding its per capita output shortfall relative to benchmark countries such as the United States to previously unimaginable levels.

This study provides one of the first attempts to systematically assess the long-run development costs of institutional breakdowns. Given its inherent limitations, four related issues remain unclear. First, why do some societies fall into the trap of institutional breakdowns while others manage to attain stable, broad-based, and enduring de jure and de facto political institutions? Second, do institutional breakdowns affect the proximate causes of growth and development such as human capital formation, physical capital formation, and demographic changes? Third, how long does it take for societies to recover economically from institutional breakdowns? And fourth, are institutional breakdowns outside Argentina fundamentally different and, if so, in what ways? Given the limitations inherent in this paper, these perplexing questions provide fruitful venues for future research.

Availability of data and materials

If the paper is accepted for publication, the dataset will be uploaded onto the data repository (i.e. Harvard Dataverse) with the full statistical code of the results to facilitate and encourage the replication.

Notes

5 U.S. 1 Cranch 137 (1803).Wenzel (2010, 336–37) offers a very clear explanation for the disconnection between the 1853 Constitution with its subsequent amendments and the long tradition of Spanish colonial institutions:

The 1853/60 constitution was accepted by the interior provinces only because it was federalist… But Argentine federalism was different. Although the founding élites of 1853 were mostly federalist, Argentina as a whole never embraced such a belief. Local caudillos, regional interests, and the porteño leadership embraced only a pragmatic federalism, designed to protect their own power from competitors… The political and economic order of the postconstitutional era was decidedly not liberal. Concessions to freedom were calculated, not principled, as the ruling oligarchs shrewdly applied the personal guarantees necessary to attract immigration and capital, while using the state to foment economic growth. From 1853/1860 to the populist takeover of 1916, the constitution was driven and manipulated by the oligarchy. Economic growth of the country was really the economic prosperity for the élite. The system was economically liberal, but not in a civil or political sense… As long as they could stay in power, and as long as the money kept rolling in, the oligarchs maintained the veneer of a liberal order. But as soon as they started to lose power through electoral reform and the subsequent middle class erosion of their power base, and the economy faltered, the proverbial iron fist broke out of the velvet glove, and the military formally broke the constitutional order in 1930.

After the presidencies of Bartolomé Mitre (Liberal Party of Corrientes, or Partido Liberal de Corrientes) and Domingo Sarmiento (an independent candidate) ended in 1868 and 1874, respectively, the subsequent presidents were elected from the conservative elites. Their party, PAN, consistently manipulated elections using fraudulent techniques and voter intimidation. An English newspaper in 1890 highlighted the persistence of electoral fraud, describing the rise of Miguel Juárez Celman to the presidential office: “Today, there are dozens of men in government who are publicly accused of malpractice, who in any civilized country would be quickly punished with imprisonment, and yet none of them have been brought to justice. Meanwhile, Celman is at liberty to enjoy the comfort of his farm, and no one thinks to punish him” (Pigna 2016).

Before the rise of Perón, Supreme Court turnover mainly occurred when justices died, retired, or voluntarily resigned. The purge of Supreme Court justices during Perón’s rule in 1946–55 changed the causes of turnover (Gallo and Alston 2008). Before 1945, 38 changes of justices are recorded, 12 of which are accounted for by retirement, 20 by death, and 6 by voluntary resignation. After Perón’s rise to power, 65 changes of justices are recorded. Only four Supreme Court justice changes are accounted for by death and just one by retirement. The remaining 59 changes resulted from voluntary resignation (18 changes), involuntary resignation (20 changes), impeachment (4 changes), or forced removal (17 changes).

One such form of propaganda was the assignment of Eva Perón’s autobiography, La Razón de Mi Vida, as compulsory reading in Argentine schools.

Acemoglu and Robinson (2006b, 7) write, “The political history of Argentina reveals an extraordinary pattern where democracy was created in 1912, undermined in 1930, re-created in 1946, undermined in 1955, fully re-created in 1973, undermined in 1976, and finally re-established in 1983. In between were various shades of nondemocratic governments ranging from restricted democracies to full military regimes. The political history of Argentina is one of incessant instability and conflict. Economic development, changes in the class structure and rapidly widening inequality, which occurred as a result of the export boom from the 1880’s, coincided with pressure on the traditional political elite to open the system. But, the nature of Argentine society meant that democracy was not stable.”

It is furthermore assumed that \(\sum\nolimits_

Acemoglu and Robinson (2006a, 326) illustrate the persistence of de jure and de facto political power, drawing on the Southern Equilibrium in the aftermath of the US Civil War: “One of the best examples of the persistence of economic institutions as a consequence of the persistence of de facto power comes from the southern United States. In the antebellum period, the South was particularly poor…; had an urbanization rate of 9 percent as opposed to 30 percent in the Northeast; had relatively few railroads or canals; and was technologically stagnant. The economy was based on slavery and labor-intensive cotton production, and in many states it was illegal to teach slaves how to read and write. After the Civil War, with the abolition of slavery and enfranchisement of the freed slaves, one might have anticipated a dramatic change in economic institutions. Instead, what emerged was a labor-intensive, low-wage, low-education, and repressive economy that in many ways looked remarkably like that of the antebellum South. Slavery was gone, but in its place were the Ku Klux Klan and Jim Crow. Why did the Southern Equilibrium persist? Despite losing the Civil War, antebellum elites managed to sustain their political control of the South, particularly after the reconstruction ended in 1877… They successfully blocked the economic reforms that might have undermined this power… They also derailed political reforms they opposed, and freed slaves were quickly disenfranchised through the use of literacy tests and poll taxes. Consequently, although slavery was abolished, Southern elites still possessed considerable de facto power through their control over economic resources, their greater education, and their relative ability to engage in collective action.”.

McCloskey (2016, 69) further illustrates the necessity of social ethics for institutional development: “I don’t think institutions work without a great deal of social ethics—think of the constitutions of the USSR or the Russian Federation; think of the laws on rape being the same in Uganda and in the United Kingdom, with very different results. Abraham Lincoln declared in the first of the Lincoln–Douglas debates of 1858, ‘With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed. Consequently, he who molds public sentiment goes deeper than he who enacts statues or pronounces decisions. He makes statutes and decisions possible or impossible to be executed’” (emphasis in original).

References

- Abadie A, Diamond A, Hainmueller J (2010) Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. J Am Stat Assoc 105(490):493–505 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2000) Why did the west extend the Franchise? Democracy, inequality, and growth in historical perspective. Quart J Econ 115(4):1167–1199 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2001) Inefficient redistribution. Am Polit Sci Rev 95(3):649–661 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2006a) De Facto political power and institutional persistence. Am Econ Rev 96(2):325–330 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2006b) Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge University Press, New York Google Scholar

- Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2012) Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Business, New York Google Scholar

- Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson JA (2001) The colonial origins of comparative development: an empirical investigation. Am Econ Rev 91(5):1369–1401 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson JA (2002) Reversal of fortune: geography and institutions in the making of modern world income distribution. Quart J Econ 117(4):1231–1294 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson JA, Thaicharoen Y (2003) Institutional causes, macroeconomic symptoms: volatility, crises and growth. J Monetary Econ 50(1):49–123 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson JA, Yared P (2005) From education to democracy? Am Econ Rev 95(2):44–49 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Adelman J (1992) Reflections on Argentine labour and the rise of Perón. Bull Latin Am Res 11(3):243–259 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Adelman J (1994) Frontier development: land, labour, and capital on the wheatlands of Argentina and Canada, 1890–1914. Oxford University Press, New York BookGoogle Scholar

- Adelman J (1999) Republic of capital: Buenos Aires and the legal transformation of the atlantic world. Stanford University Press, Stanford Google Scholar

- Aghion P, Caroli E, García-Peñalosa C (1999) Inequality and economic growth: the perspective of the new growth theories. J Econ Lit 37(4):1615–1660 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Alesina A, Rodrik D (1994) Distributive politics and economic growth. Quart J Econ 109(2):465–490 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Alesina A, Devleeschauwer A, Easterly W, Kurlat S, Wacziarg R (2003) Fractionalization. J Econ Growth 8(2):155–194 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Algan Y, Cahuc P (2010) Inherited trust and growth. Am Econ Rev 100(5):2060–2092 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Alhadeff P (1989) Social welfare and the slump: Argentina in the 1930s. In: Platt DCM (ed) Social welfare, 1850–1950: Australia, Argentina and Canada Compared. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 169–178 ChapterGoogle Scholar

- Alston LJ, Gallo AA (2010) Electoral fraud, the rise of Perón and demise of checks and balances in Argentina. Explor Econ Hist 47(2):179–197 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Alston LJ, Mueller B (2006) Pork for policy: executive and legislative exchange in Brazil. J Law Econ Organ 22(1):87–114 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Andrien KJ (1982) The sale of fiscal offices and the decline of royal authority in the viceroyalty of Peru, 1633–1700. Hisp Am Hist Rev 62(1):49–71 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Andrien KJ (1984) Corruption, inefficiency, and imperial decline in the seventeenth-century viceroyalty of Peru. Americas 41(1):1–20 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Arceneaux CL (1997) Institutional design, military rule, and regime transition in Argentina (1976–1983): an extension of the remmer thesis. Bull Latin Am Res 16(3):327–350 Google Scholar

- Arellano M (1987) Computing robust standard errors for within-groups estimators. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 49(4):431–434 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ashraf Q, Galor O (2013) The ‘Out of Africa’ hypothesis, human genetic diversity, and comparative economic development. Am Econ Rev 103(1):1–46 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Austin G (2008) The ‘Reversal of Fortune’ thesis and the compression of history: perspectives from African and comparative economic history. J Int Dev 20(8):996–1027 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Azcuy Ameghino E (2002) La otra historia: Economía, Estado y Sociedad en el Río de la Plata Colonial. Ediciones Imago Mundi, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Bambaci J, Saront T, Tommasi M (2002) The political economy of economic reforms in Argentina. J Policy Reform 5(2):75–88 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Barro RJ (1999) Determinants of democracy. J Polit Econ 107(S6):158–183 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Barro RJ, Lee JW (2013) A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. J Dev Econ 104:184–198 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Baskes J (2000) Indians, merchants, and markets: a reinterpretation of the repartimiento and Spanish-Indian economic relations in Colonial Oaxaca, 1750–1821. Stanford University Press, Stanford Google Scholar

- Bayle C (1952) Los cabildos seculares en la América española. Sapientia, Madrid Google Scholar

- Becker SO, Woessmann L (2009) Was weber wrong? A human capital theory of protestant economic history. Quart J Econ 124(2):531–596 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Berkowitz D, Pistor K, Richard J-F (2003a) Economic development, legality, and the transplant effect. Eur Econ Rev 47(1):165–195 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Berkowitz D, Pistor K, Richard J-F (2003b) The transplant effect. Am J Comp Law 51(1):163–203 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bértola L, Ocampo JA (2012) The economic development of Latin America since independence. Oxford University Press, New York BookGoogle Scholar

- Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S (2004) How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Quart J Econ 119(1):249–275 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bethell L (1993) Argentina since independence. Cambridge University Press, New York BookGoogle Scholar

- Bloom DE, Sachs JD (1998) Geography, demography, and economic growth in Africa. Brook Pap Econ Act 1998(2):207–295 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bollen KA (1990) Political democracy: conceptual and measurement traps. Stud Comp Int Dev 25(1):7–24 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bolt J, van Zanden JL (2014) The Maddison project: collaborative research on historical national accounts. Econ Hist Rev 67(3):627–651 Google Scholar

- Brennan JP, Rougier M (2009) The politics of national capitalism: Peronism and Argentine Bourgeoisie, 1946–1976. Penn State Press, University Park Google Scholar

- Bruhn M, Gallego FA (2012) Good, bad, and ugly colonial activities: do they matter for economic development? Rev Econ Stat 94(2):433–461 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Buchanan PG (1985) State corporatism in Argentina: labor administration under Perón and Onganía. Latin Am Res Rev 20(1):61–95 Google Scholar

- Burkholder MA, Chandler DS (1977) From impotence to authority: the Spanish crown and the American Audiencias, 1687–1808. University of Missouri Press, Columbia Google Scholar

- Calvo E, Murillo MV (2004) Who delivers? Partisan clients in the Argentine electoral market. Am J Polit Sci 48(4):742–757 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cameron AC, Trivedi PK (2005) Microeconometrics: methods and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge BookGoogle Scholar

- Cameron AC, Gelbach JB, Miller DL (2011) Robust inference with multiway clustering. J Bus Econ Stat 29(2):238–249 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Campos NF, Karanasos MG, Tan B (2012) Two to tangle: financial development, political instability and economic growth in Argentina. J Bank Finance 36(1):290–304 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cantón D (1973) Elecciones y partidos políticos en la Argentina: Interpretación y balance, 1910–1966. Siglo XXI, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Cantú F, Saiegh SM (2011) Fraudulent democracy? An analysis of Argentina’s infamous decade using supervised machine learning. Polit Anal 19(4):409–433 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chavez RB (2004) the evolution of judicial autonomy in Argentina: establishing the rule of law in an ultrapresidential system. J Latin Am Stud 36(3):451–478 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ciria A (1974) Parties and power in modern Argentina 1930–1946. SUNY Press, Albany Google Scholar

- Clague C, Keefer P, Knack S, Olson M (1999) Contract-intensive money: contract enforcement, property rights, and economic performance. J Econ Growth 4(2):185–211 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Collier RB, Collier D (2004) Shaping the political arena: Critical junctures, the labor movement and regime dynamics in Latin America. Princeton University Press, Princeton Google Scholar

- Colomer JM (2004) Taming the tiger: voting rights and political instability in Latin America. Latin Am Polit Soc 46(2):29–58 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cook CJ (2014) The role of lactase persistence in precolonial development. J Econ Growth 19(4):369–406 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cortés Conde R (1998a) Fiscal Crisis and Inflation in XIX Century Argentina. Documento de Trabajo 18. Universidad de San Andrés, Buenos Aires

- Cortés Conde R (1998b) Progreso y declinación de la economía argentina: Un análisis histórico institucional. Fondo de Cultura Económica, Buenos Aires

- Crassweller RD (1988) Perón and the Enigmas of Argentina. Norton, New York Google Scholar

- Crawley E (1984) A house divided: Argentina, 1880–1980. St. Martin’s Press, New York Google Scholar

- Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16(3):297–334 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Davis P (2002) Estimating multi-way error components models with unbalanced data structures. J Econom 106(1):67–95 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- de Privitello L, Romero LA (2000) Grandes discursos de la historia Argentina. Aguilar, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- de Velasco JAM (1983) Relación y documentos de gobierno del virrey del Perú, José A. Manso de Velasco, conde de Superunda (1745–1761). Editorial CSIC, Madrid

- Dell M, Jones BF, Olken BA (2012) Temperature shocks and economic growth: evidence from the last half century. Am Econ J: Macroecon 4(3):66–95 Google Scholar

- della Paolera G, Taylor AM (1999) Economic recovery from the Argentine great depression: institutions, expectations, and the change of macroeconomic regime. J Econ Hist 59(3):567–599 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Di Tella G (1983) Argentina under Perón, 1973–76: the nation’s experience with a labour-based government. Macmillan, London BookGoogle Scholar

- Di Tella TS (1998) Historia social de la Argentina contemporanea. Troquel, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Di Tella G, Platt DCM (eds) (1986) The political economy of Argentina, 1880–1946. Palgrave Macmillan, London Google Scholar

- Di Tella G, Zymelman M (1967) Las etapas del desarrollo económico argentino. Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Di Tella R, Glaeser EL, Llach L (2013) Introduction to Argentine exceptionalism exceptional Argentina. Latin Am Econ Rev 27(1):1–22 Google Scholar

- Díaz Alejandro CF (1970) Essays on the economic history of the Argentine Republic. Yale University Press, New Haven Google Scholar

- Díaz Alejandro CF (1985) Argentina, Australia and Brazil before 1929. In: Platt DCM, di Tella G (eds) Argentina, Australia and Canada: studies in comparative development. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 95–109 ChapterGoogle Scholar

- Díaz Bessone RG (1986) Guerra revolucionaria en la Argentina (1959–1978). Editorial Fraterna, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Duncan T, Fogarty J (1984) Australia and Argentina: on parallel paths. Melbourne University Press, Melbourne Google Scholar

- Eaton KH (2002) Fiscal policy making in the Argentine legislature. In: Morgenstern S, Nacif B (eds) Legislative politics in Latin America. Duke University Press, Durham, pp 287–314 ChapterGoogle Scholar

- Eder PJ (1949) Impact of the common law on Latin America. Miami Law Quart 4(4):435–440 Google Scholar

- Elena E (2007) Peronist consumer politics and the problem of domesticating markets in Argentina, 1943–1955. Hisp Am Hist Rev 87(1):111–149 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Elizagaray AA (1985) The political economy of a populist government: Argentina, 1943–55. PhD diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Engerman SL, Sokoloff KL (1997) Factor endowments, institutions and differential paths of growth among the new world economies. In: Haber S (ed) How Latin America fell behind. Stanford University Press, Stanford, pp 260–306 Google Scholar

- Engerman SL, Sokoloff KL (2005) The evolution of suffrage institutions in the new world. J Econ Hist 65(4):891–921 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Evans G, Rose P (2007) Support for democracy in Malawi: does schooling matter? World Dev 35(5):904–919 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fayt CA (1967) La naturaleza del Peronismo. Editorial Viracocha, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Feenstra RC, Inklaar R, Timmer MP (2015) The next generation of the Penn World Table. Am Econ Rev 105(10):3150–3182 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Feld LP, Voigt S (2003) Economic growth and judicial independence: cross-country evidence using a new set of indicators. Eur J Polit Econ 19(3):497–527 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ferns HS (1969) Argentina. Praeger, New York Google Scholar

- Ferrero RA (1976) Del fraude a soberania popular, 1938–1946. La Bastilla, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Feyrer J, Sacerdote B (2009) Colonialism and modern income: islands as natural experiments. Rev Econ Stat 91(2):245–262 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Földvári P (2016) De Facto versus de Jure Political Institutions in the long-run: a multivariate analysis, 1820–2000. Soc Indic Res 130(2):759–777 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Friedman M (1962) Capitalism and freedom. University of Chicago Press, Chicago Google Scholar

- Fukuyama F (ed) (2008) Falling behind: explaining the development gap between Latin America and the United States. Oxford University Press, Oxford Google Scholar

- Fukuyama F (2014) Political order and political decay: from the industrial revolution to the globalization of democracy. Macmillan, London Google Scholar

- Gallo E (1983) La pampa gringa: La colonización agrícola en Santa Fe (1870–1875). Editorial Sudamericana, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Gallo E (1993) Society and politics, 1880–1916. In: Bethell L (ed) Argentina since independence. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 79–112 ChapterGoogle Scholar

- Gallo AA, Alston LJ (2008) Argentina’s abandonment of the rule of law and its aftermath. Wash Univ J Law Policy 26:153–182 Google Scholar

- Gallup JL, Sachs JD, Mellinger AD (1999) Geography and economic development. Int Reg Sci Rev 22(2):179–232 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Garavaglia JC, Gelman JD (1995) Rural history of the Rio de la Plata, 1600–1850: results of a historiographical renaissance. Latin Am Res Rev 30(3):75–105 Google Scholar

- Garay AF (1991) Federalism, the judiciary, and constitutional adjudication in Argentina: a comparison with the US constitutional model. Univ Miami Inter-Am Law Rev 22(2–3):161–202 Google Scholar

- García Hamilton JI (2005) Historical reflections on the splendor and decline of Argentina. Cato J 25(3):521–540 Google Scholar

- Gerchunoff P, Díaz Alejandro CF (1989) Peronist economic policies, 1946–1955. In: Di Tella G, Dornbusch R (eds) The political economy of Argentina, 1946–1983. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 59–88 ChapterGoogle Scholar

- Gerchunoff P, Fajgelbaum P (2006) Por qué Argentina no fue Australia? Una hipótesis sobre un cambio de rumbo. Siglo XXI, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Germani G (1966) Mass immigration and modernization in Argentina. Stud Comp Int Dev 2(11):165–182 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Germani G (1973) El surgimiento del peronismo: El rol de los obreros—y de los migrantes internos. Desarrollo Económico 13(51):435–488 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gibson EL (1997) The populist road to market reform: policy and electoral coalitions in Mexico and Argentina. World Polit 49(3):339–370 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Glaeser EL, Ponzetto GAM, Shleifer A (2007) Why does democracy need education? J Econ Growth 12(2):77–99 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Goel RK, Nelson MA (2005) Economic freedom versus political freedom: cross-country influences on corruption. Aust Econ Pap 44(2):121–133 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Goldwert M (2014) Democracy, militarism, and nationalism in Argentina, 1930–1966: An interpretation. University of Texas Press, Austin Google Scholar

- Golte J (1980) Repartos y rebeliones: Túpac Amaru y las contradicciones de la economía colonial. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, Lima Google Scholar

- Gomez I (2000) Declaring unconstitutional a constitutional amendment: the Argentine judiciary forges ahead. Univ Miami Inter-Am Law Rev 31(1):93–119 Google Scholar

- Gorodnichenko Y, Roland G (2011) Which dimensions of culture matter for long-run growth? Am Econ Rev 101(3):492–498 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Guardado J (2016) Office-selling, corruption and long-term development in Peru. PhD diss., New York University

- Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2006) Does culture affect economic outcomes? J Econ Perspect 20(2):23–48 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gwartney JD, Lawson RA, Holcombe RG (1999) Economic freedom and the environment for economic growth. J Inst Theor Econ 155(4):643–663 Google Scholar

- Halperín Donghi T (1970) Historia contemporánea de América Latina. Alianza, Madrid Google Scholar

- Halperín Donghi T (1991) The Buenos Aires landed class and the shape of politics in Argentina, 1820–1930. Center for Latin America Discussion Paper 85, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee

- Halperín Donghi T (1995) The Buenos Aires landed class and the shape of Argentine politics (1820–1930). In: Huber E, Safford F (eds) Agrarian structure and political power: landlord and peasant in the making of Latin America. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, pp 39–66 Google Scholar

- Halperín Donghi T (2004) La república imposible (1930–1945). Ariel, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Hansen CB (2007) Asymptotic properties of a robust variance matrix estimator for panel data when T is large. J Econom 141(2):597–620 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Haring CH (1972) El imperio español en las Indias. Solar Hachette, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Horowitz J (1990) Industrialists and the rise of Perón, 1943–1946: some implications for the conceptualization of populism. Americas 47(2):199–217 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Iaryczower M, Spiller PT, Tommasi M (2002) Judicial independence in unstable environments, Argentina 1935–1998. Am J Polit Sci 46(4):99–716 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ilsley LL (1952) The Argentine constitutional revision of 1949. J Polit 14(2):224–240 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jones MP, Saiegh S, Spiller PT, Tommasi M (2002) Amateur legislators-professional politicians: the consequences of party-centered electoral rules in a federal system. Am J Polit Sci 46(3):656–669 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kelly JM (1992) A short history of western legal theory. Oxford University Press, New York Google Scholar

- Kenn Farr W, Lord RA, Wolfenbarger JL (1998) Economic freedom, political freedom, and economic well-being: a causality analysis. Cato J 18(2):247–262 Google Scholar

- Kenworthy E (1975) Interpretaciones ortodoxas y revisionistas del apoyo inicial del peronismo. Desarrollo Económico 56(14):749–763 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kézdi G (2004) Robust standard errors estimation in fixed-effects models. Hung Stat Rev Spec 9:95–116 Google Scholar

- Kloek T (1981) OLS estimation in a model where a microvariable is explained by aggregates and contemporaneous disturbances are equicorrelated. Econometrica 49(1):205–207 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Knack S, Keefer P (1995) Institutions and economic performance: cross-country tests using alternative institutional measures. Econ Politics 7(3):207–227 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kovac M, Spruk R (2017) Persistent effects of colonial institutions on human capital formation and long-run development: local evidence from regression discontinuity design in Argentina. Presented at the Society for Institutional and Organizational Economics, Columbia University, New York

- Krueger AO (2002) Political economy of policy reform in developing countries. MIT Press, Cambridge Google Scholar

- Kydland FE, Zarazaga CEJM (2002) Argentina’s lost decade. Rev Econ Dyn 5(1):152–165 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- La Porta R, López-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A (2008) The economic consequences of legal origins. J Econ Lit 46(2):285–332 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Liang K-Y, Zeger SL (1986) Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 73(1):13–22 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lipset SM (1959) Some social requisites of democracy: economic development and political legitimacy. Am Polit Sci Rev 53(1):69–105 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Little W (1973) Electoral aspects of Peronism, 1946–1954. J Interam Stud World Aff 15(3):267–284 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Llach JJ (1985) La Argentina que no fue, vol 1. Autores Editores, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Lupu N, Stokes S (2010) Democracy, interrupted: regime change and partisanship in twentieth-century Argentina. Elect Stud 29(1):91–104 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lynch J (1955) Intendants and cabildos in the viceroyalty of La Plata, 1782–1810. Hisp Am Hist Rev 35(3):337–362 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Maddison A (2007a) The world economy. Vol. 1: a millennial perspective. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris Google Scholar

- Maddison A (2007b) The world economy. Vol. 2: historical statistics. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris Google Scholar

- Mankiw NG, Romer D, Weil DN (1992) A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Q J Econ 107(2):407–437 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Manzetti L (1993) Institutions, parties, and coalitions in Argentine politics. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh Google Scholar

- Maravall JM, Przeworski A (eds) (2003) Democracy and the rule of law. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Google Scholar

- Marshall MG, Gurr TR, Jaggers K (2013) Polity IV project: political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2012. Center for Systemic Peace, Vienna Google Scholar

- Maseland RKJ, Spruk R (2017) Premature democratization, premature deindustrialization. Paper presented at the Society for Institutional and Organizational Economics, Columbia University, New York

- Matsushita H (1983) Movimiento obrero argentino, 1930–1945: Sus proyecciones en los orígenes del peronismo. Siglo Veinte, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Mazzuca S (2007) Southern Cone Leviathans: state formation in Argentina and Brazil. PhD diss., University of California at Berkeley

- McCloskey DN (2016) The humanities are scientific: a reply to the defenses of economic neo-institutionalism. J Inst Econ 12(1):63–78 Google Scholar

- Michels R (1911) Political parties: a sociological study of the oligarchic tendencies of modern democracy. Batoche, Kitchener Google Scholar

- Miller J (1997) Judicial review and constitutional stability: a sociology of the US model and its collapse in Argentina. Hastings Int Comp Law Rev 21:77–126 Google Scholar

- Miller J (2003) A typology of legal transplants: using sociology, legal history and Argentine examples to explain the transplant process. Am J Comp Law 51(4):839–885 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mirow MC (2004) Latin American law: a history of private law and institutions in Spanish America. University of Texas Press, Austin Google Scholar

- Mohtadi H, Roe TL (2003) Democracy, rent seeking, public spending and growth. J Public Econ 87(3–4):445–466 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Molinelli NG, Palanza MV, Sin G (1999) Congreso, presidencia y justicia en Argentina. Temas, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Montaño SMD (1957) The constitutional problem of the Argentine Republic. Am J Comp Law 6(2–3):340–345 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Moreno Cebrián A (1976) Venta y beneficios de los corregimientos peruanos. Revista de Indias 36(143–44):213–246 Google Scholar

- Moulton BR (1986) Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates. J Econom 32(3):385–397 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Moulton BR (1990) An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units. Rev Econ Stat 72(2):334–338 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mukand S, Rodrik D (2015) The political economy of liberal democracy. Working Paper 21540, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA

- Mukerjee A (2008) La negociación de un compromiso: la mita de las minas de plata de San Agustín de Huantajaya, Tarapacá, Perú (1756–1766). Bull l’Institut Français d’Études Andines 37(1):217–225 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Munck R (1985) The ‘Modern’ military dictatorship in Latin America: the case of Argentina (1976–1982). Latin Am Perspect 12(4):41–74 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Murmis M, Portantiero JC (1972) Estudios sobre los orígenes del peronismo, vol 2. Siglo XXI, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Murphy KM, Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1993) Why is rent-seeking so costly to growth? Am Econ Rev 83(2):409–414 Google Scholar

- Negretto G (2009) Political parties and institutional design: explaining constitutional choice in Latin America. Br J Polit Sci 39(1):117–139 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge BookGoogle Scholar

- North DC, Wallis JJ, Weingast BR (2009) Violence and social orders: a conceptual framework for interpreting recorded human history. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge BookGoogle Scholar

- Nunn N, Puga D (2012) Ruggedness: the blessing of bad geography in Africa. Rev Econ Stat 94(1):20–36 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nunn N, Qian N (2011) The potato’s contribution to population and urbanization: evidence from a historical experiment. Quart J Econ 126(2):593–650 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- O’Connell A (1986) Free trade in one (primary producing) country: the case of Argentina in the 1920s. In: Di Tella G, Platt DCM (eds) The political economy of Argentina, 1880–1946. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 74–94 ChapterGoogle Scholar

- O’Donnell GA (1973) Modernization and bureaucratic-authoritarianism: studies in South American politics. University of California Press, Irvine Google Scholar

- Olson M (1982) The rise and decline of nations: economic growth, stagflation, and social rigidities. Yale University Press, New Haven Google Scholar

- Osiel MJ (1995) Dialogue with dictators: judicial resistance in Argentina and Brazil. Law Soc Inquiry 20(2):481–560 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ots Capdequí JM (1943) Manual de historia del derecho español en las Indias y del derecho propiamente indiano. Instituto de Historía del Derecho Argentino, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Owen F (1957) Perón: his rise and fall. Cresset Press, London Google Scholar

- Pande R, Udry CR (2005) Institutions and development: a view from below. Economic growth center discussion paper 928, Yale University, New Haven, CT

- Pellet Lastra A (2001) Historia Política de la Corte (1930–1990). AdHoc, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Pemstein D, Meserve SA, Melton J (2010) Democratic compromise: a latent variable analysis of ten measures of regime type. Polit Anal 18(4):426–449 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Pepper JV (2002) Robust inferences from random clustered samples: an application using data from the panel study of income dynamics. Econ Lett 75(3):341–345 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Peralta-Ramos M (1992) The political economy of Argentina: power and class since 1930. Westview, Boulder Google Scholar

- Pereira S (1983) En tiempos de la república agropecuaria (1930–1943). Centro Editor de América Latina, Buenos Aires

- Pfeffermann D, Nathan G (1981) Regression analysis of data from a clustered sample. J Am Stat Assoc 76(375):681–689 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Pigna F (2016) Miguel Juárez Celman y la revolución de 1890. El Historiador, Buenos Aires. https://www.elhistoriador.com.ar/miguel-juarez-celman-y-la-revolucion-de-1890/

- Pion-Berlin D (1985) The fall of military rule in Argentina: 1976–1983. J Interam Stud World Aff 27(2):55–76 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Platt DCM, Di Tella G (eds) (1985) Argentina, Australia and Canada: studies in comparative development, 1870–1965. Palgrave Macmillan, London Google Scholar

- Potash RA (1996) The army and politics in Argentina, 1962–1973. Vol. 3. From Frondizi’s fall to the peronist restoration. Stanford University Press, Stanford Google Scholar

- Prado F (2009) In the shadows of empires: trans-imperial networks and colonial identity in Bourbon Rio de la Plata (c. 1750–c. 1813). PhD diss., Emory University

- Prados de la Escosura L, Sanz-Villarroya I (2009) Contract enforcement, capital accumulation, and Argentina’s long-run decline. Cliometrica 3(1):1–26 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Przeworski A, Limongi F (1997) Modernization: theories and facts. World Polit 49(2):155–183 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Psacharopoulos G (1994) Returns to investment in education: a global update. World Dev 22(9):1325–1343 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Pucciarelli AR (1986) El capitalismo agrario pampeano, 1880–1930: La formación de una nueva estructura de clases en la Argentina moderna. Hyspamérica, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Rennie YF (1945) The Argentine Republic. Macmillan, New York BookGoogle Scholar

- Ribas AP (2000) Argentina, 1810–1880: Un milagro de la historia. VerEdit, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Robinson JA (2013) measuring institutions in the trobriand islands: a comment on Voigt’s paper. J Inst Econ 9(1):27–29 Google Scholar

- Rock D (1975) Politics in Argentina, 1890–1930: the rise and fall of radicalism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge BookGoogle Scholar

- Rock D (1987) Argentina, 1516–1987: from Spanish colonization to Alfonsín. University of California Press, Berkeley Google Scholar

- Rock D (1993) Authoritarian Argentina: the nationalist movement, its history and its impact. University of California Press, Berkeley Google Scholar

- Rodrik D (2016) Premature deindustrialization. J Econ Growth 21(1):1–33 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Roe MJ (1998) Backlash. Columbia Law Rev 98(1):217–241 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Romero RJ (1998) Fuerzas armadas: La alternativa de la derecha para el acceso al poder (1930–1976). Centro de Estudios Unión para la Nueva Mayoría, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Romero LA (2013) A history of Argentina in the twentieth century, Rev edn. Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park Google Scholar

- Rosa JM (1965) Historia Argentina, vol 1. Juan C. Granda, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Rosenn KS (1990) The success of constitutionalism in the United States and its failure in Latin America: an explanation. Univ Miami Inter-Am Law Rev 22(1):1–39 Google Scholar

- Rouquié A (1982) Hegemonía militar, estado y dominación social. In: Rouquie A (ed) Argentina, hoy. Siglo XXI, Mexico City, pp 11–50 Google Scholar

- Sabato H (2001) On political citizenship in nineteenth-century Latin America. Am Hist Rev 106(4):1290–1315 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sábato JF (1988) La clase dominante en la Argentina moderna: Formación y características. CISEA, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Sachs JD (1990) Social conflict and populist policies in Latin America. In: Brunetta R, Dell’Aringa C (eds) Labor relations and economic performance. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 137–169 Google Scholar

- Sachs JD, Malaney P (2002) The economic and social burden of malaria. Nature 415(6872):680–685 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Saint Paul G, Verdier T (1996) Inequality, redistribution and growth: a challenge to the conventional political economy approach. Eur Econ Rev 40(3–5):719–728 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Samuels D, Snyder R (2001) The value of a vote: malapportionment in comparative perspective. Br J Polit Sci 31(4):651–671 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sánchez-Alonso B (2000) Those who left and those who stayed behind: explaining emigration from the regions of Spain, 1880–1914. J Econ Hist 60(3):730–755 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sanguinetti HJ (1988) La democracia ficta, 1930–1938. Ediciones La Bastilla, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Sanz-Villarroya I (2005) The convergence process of Argentina with Australia and Canada: 1875–2000. Explor Econ Hist 42(3):439–458 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sanz-Villarroya I (2007) La ‘belle époque’ de la economía Argentina, 1875–1913. Acciones e Investigaciones Sociales 23(1):115–138 Google Scholar

- Scartascini C, Tommasi M (2012) the making of policy: institutionalized or not? Am J Polit Sci 56(4):787–801 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Schilizzi Moreno HA (1973) Argentina contemporánea: Fraude y entrega. Plus Ultra, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Shirley MM (2013) Measuring institutions: how to be precise though vague. J Inst Econ 9(1):31–33 Google Scholar

- Shumway N (1991) The invention of Argentina. University of California Press, Berkeley Google Scholar

- Smith PH (1969) Social mobilization, political participation, and the rise of Juan Perón. Polit Sci Quart 84(1):30–49 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Smith PH (1974) Argentina and the failure of democracy: conflict among political elites, 1904–1955. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison Google Scholar

- Smulovitz C (1991) En busca de la fórmula perdida: argentina, 1955–1966. Desarrollo Económico 31(121):113–124 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Snow PG (1965) Argentine radicalism: the history and doctrine of the radical civil union. University of Iowa Press, Des Moines Google Scholar

- Sokoloff KL, Engerman SL (2000) History lessons: institutions, factors, endowments, and paths of development in the new world. J Econ Perspect 14(3):217–232 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Solberg CE (1987) The prairies and the pampas: Agrarian policy in Canada and Argentina, 1880–1930. Stanford University Press, Stanford Google Scholar

- Spiller PT, Tommasi M (2003) The institutional foundations of public policy: a transactions approach with application to Argentina. J Law Econ Organ 19(2):281–306 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Spinelli ME (2005) Los vencedores vencidos: El antiperonismo y la “revolución libertadora”. Biblos, Buenos Aires Google Scholar

- Spinesi L (2009) Rent-seeking bureaucracies, inequality, and growth. J Dev Econ 90(2):244–257 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Spolaore E, Wacziarg R (2009) The diffusion of development. Quart J Econ 124(2):469–529 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Spolaore E, Wacziarg R (2013) How deep are the roots of economic development? J Econ Lit 51(2):325–369 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Spruk R (2016) Institutional transformation and the origins of world income distribution. J Comp Econ 44(4):936–960 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sturzenegger F, Tommasi M (1994) The distribution of political power, the costs of rent-seeking, and economic growth. Econ Inq 32(2):236–248 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Summerhill WR (2000) Institutional determinants of railroad subsidy and regulation in imperial Brazil. In: Haber S (ed) Political institutions and economic growth in Latin America: essays in policy, history and political economy. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, pp 21–67 Google Scholar

- Szusterman C (1993) Frondizi and the politics of developmentalism in Argentina, 1955–62. Springer, New York BookGoogle Scholar

- Tabellini G (2010) Culture and institutions: economic development in the regions of Europe. J Eur Econ Assoc 8(4):677–716 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Taylor AM (1992) External dependence, demographic burdens, and Argentine economic decline after the Belle Époque. J Econ Hist 52(4):907–936 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Taylor AM (1998a) Argentina and the world capital market: saving, investment, and international capital mobility in the twentieth century. J Dev Econ 57(1):147–184 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Taylor AM (1998b) On the costs of inward-looking development: price distortions, growth, and divergence in Latin America. J Econ Hist 58(1):1–28 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Taylor AM, Williamson JG (1997) Convergence in the age of mass migration. Eur Rev Econ Hist 1(1):27–63 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Teichman J (1981) Interest conflict and entrepreneurial support for Perón. Latin Am Res Rev 16(1):144–155 Google Scholar

- Treier S, Jackman S (2008) Democracy as a latent variable. Am J Polit Sci 52(1):201–217 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Vanhanen T (2000) A new dataset for measuring democracy, 1810–1998. J Peace Res 37(2):251–265 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Vanhanen T (2003) Measures of democracy 1810–2002. Finnish Social Science Data Archive

- Vittadini Andres SN (1999) First amendment influence in Argentine Republic law and jurisprudence. Commun Law Policy 4(2):149–175 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Voigt S (2013) How (not) to measure institutions. J Inst Econ 9(1):1–26 Google Scholar

- Waisman CH (1987) Reversal of development in Argentina: postwar counterrevolutionary policies and their structural consequences. Princeton University Press, Princeton BookGoogle Scholar

- Walter RJ (1969) The intellectual background of the 1918 university reform in Argentina. Hisp Am Hist Rev 49(2):233–253 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Walter RJ (2002) The province of Buenos Aires and Argentine politics, 1912–1943. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Google Scholar

- Weingast BR (1997) The political foundations of democracy and the rule of the law. Am Polit Sci Rev 91(2):245–263 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wenzel NG (2010) Matching constitutional culture and parchment: post-colonial constitutional adoption in Mexico and Argentina. Hist Const 11:321–338 Google Scholar

- White H (1980) A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 48(4):817–838 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- White H (1984) Asymptotic theory for econometricians. Academic Press, New York Google Scholar

- Wooldridge JM (2003) Cluster-sample methods in applied econometrics. Am Econ Rev 93(2):133–138 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wynia GW (1978) Argentina in the postwar era: politics and economic policy making in a divided society. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque Google Scholar

- Yablón AS (2003) Patronage, corruption, and political culture in Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1880–1916. PhD diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Zakaria F (1997) The rise of illiberal democracy. Foreign Aff 2:22–43 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zorraquín Becú R (1978) La organización judicial Argentina en el período hispánico. Perrot, Buenos Aires Google Scholar